Consulting, convening, coding, covering new ground, plus occasional commentary.

coding

Dear Internet, can we talk? We have an information pollution problem of epic proportions.

The proliferation of digital disinformation is "the most pressing threat to global democracy," according to experts at a recent industry event at Stanford

(Scroll down to continue reading)

Misinformation and disinformation are not challenges specific to any single platform, or the responsibility of any single company: they represent a tsunami of polluted information that is threatening the fabric of trust between users and what they experience online. It’s a potential “global environmental disaster” that impacts everyone. And though the spotlight so far has mostly been on so-called “fake news,” the problem extends far beyond news and reaches into just about every aspect of our modern-day digital lives.

This is the digital equivalent of dirty carbon emissions and toxic waste being pumped into the Internet’s fragile ecosystem. Like industries that seek to externalize cost and avoid regulation, the insidious thing about information pollution is that it uses the Internet’s strengths – like openness and decentralization – against it. For each step the Internet has made toward its aspirational goals of bringing more democracy, knowledge, and civility to the world, bad actors have worked to undermine those goals for profit or power. There is a battle of epic proportions underway in the ecosystem of the Internet: profit, public relations, and politics vs. people’s trust in what they read online.

This is strong language, to be sure. But even when I believe I’ve seen the worst, there is always another person who tells me that this is only the tip of the iceberg. Researchers, data scientists, policy experts, and security specialists – they are all deeply concerned. And governments are struggling to keep up with how quickly the problem evolves: if it’s not on a specific platform yet, or in a specific country, this last year has shown that it’s only a matter of time until it appears.

So, for the impatient, here are a few takeaways that I believe are important for everyone to be thinking about in the context of solutions:

-

It’s not just fake news. This is a much bigger problem that targets people searching for health information, investment advice, employment opportunities, and more. Focusing on a single symptom distracts us from the larger disease.

-

It’s not just one platform. Much of the attention focuses on the responsibility of a single platform or service to “clean up their act;” but this is a Web-level problem that requires a holistic, collaborative, Web-level response. If you address the pollution only in one place, it just spreads elsewhere.

-

Automated, algorithmic content creation, amplification, and suppression is threatening civic discourse. And, according to people like Elon Musk and Bill Gates, it could reach catastrophic proportions with advances in artificial intelligence.

-

The fabric of trust is at stake. It’s not just about influencing one particular election, or shutting down one particular message – at a certain point, people just stop drinking the tap water because they can no longer trust it.

-

There’s an underlying political economy here. Everything is for sale – fake accounts, fake likes, fake dislikes, fake friends, fake followers, fake reviews, and – yes, of course – even fake news. And the wage gap between countries – countries increasingly connected through the Internet – means a growing pool of low-cost “mechanical turks” are for hire to create these new digital fakes.

If you’re still with me, let dive into the specifics of these (or you can jump to the end for some ways to get involved in the movement to build solutions):

Digital snake oil on SEO steroids

It would be an understatement to say people rely on the Internet to access information vital to their lives – all over the globe, individuals type their greatest hopes and fears into little boxes on the Internet expecting to receive back reliable information. But that guarantee of reliability is in jeopardy because the Web has been polluted with information that works to undermine it.

This is prevalent across Web: in search results, in search autocomplete suggestions, and in advertising that follows users around the Web encouraging them to veer off into a yet-another “click funnel” that seeks to monetize them in some way. For many years, this has been the purview of modern-day snake oil salespeople, offering alternative health advice and unregulated supplements, or a must-have seminar on how to grow your own home-based Internet business (hustling these same products, no doubt). However, as we’ve seen in recent elections, these same tactics have spread – like garbage on the side of the road that grow when unattended – to false information about newsworthy events, as well as false information about financial products.

The motivations on the production side of this pollution is mostly the same: to draw in users from search results, social networks, and other sites with the objective of generating revenue in a variety of increasingly-shady ways. For some producers, the motivation is the ego-rush of making a story go viral, and for others it’s politically motivated. For consumers, I worry that these “fakes” are similar to counterfeit watches, baseball hats and handbags, and that there will always be some market for these low-end versions of real information – either for entertainment or because it’s available at the right place (search), time (social), or price (free).

The use of automation bots to influence civic discourse

Professional journalists are increasingly forced to rely on social media to help them find and report on stories quickly. Bad actors leverage this to get false information into the mainstream media. Fake engagement numbers on social media posts can make the information appear important, which can then draw the attention of journalists. And once a verified source amplifies the misinformation, it can then spread quickly without hope of a correction – by some estimates, false information can reach ten times the audience of a retraction. Automation is increasingly used to take advantage of this. Facebook calls this “false amplification” – making posts and trends seem more popular than they really are.

On the flip side, automation is also used to shut down civic discourse. Automation is routinely observed to be targeting people with abuse and harassment with the aim of dampening or deterring their messages, sowing confusion among groups, or simply “spamming” conversations as to make them impossible to follow. Increasingly, it’s not only used to deter messages but to shut down certain voices entirely, for example women, minorities and LGBTQ2S+ communities. This use of automation is threatening to drive a stake through the heart of one of the Internet’s biggest aspirations: helping people to connect and find a common voice and common cause.

These false amplification and dampening networks are evolving quickly, which makes them challenging to identify and neutralize. More so because they increasingly come in the form of “cyborgs” – a mix of automation and human control – which can avoid many current models for detection. And the problem appears to be growing, not shrinking, according to much of the recent academic research.

Everything is for sale

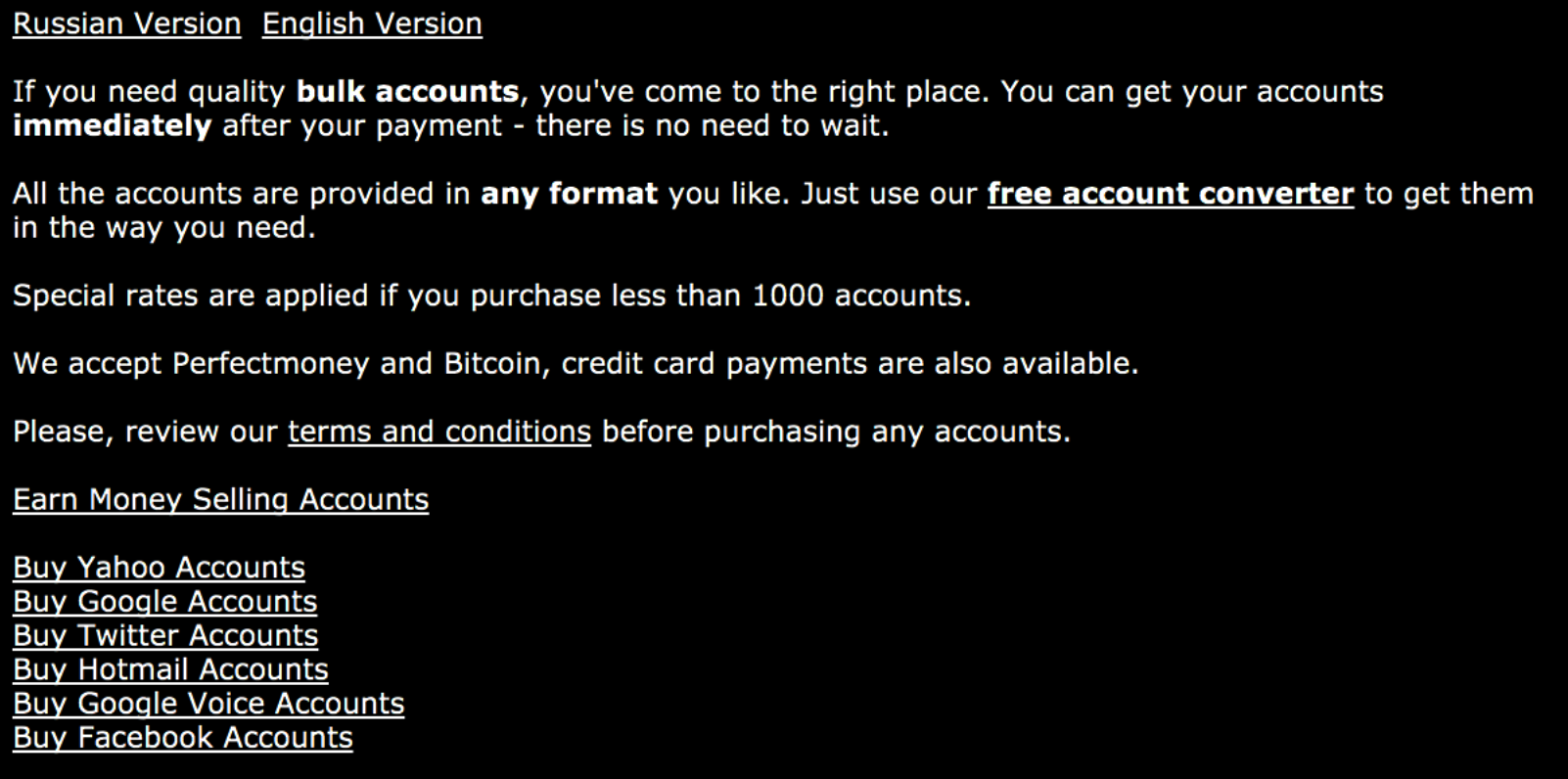

This automation is increasingly available because almost anything is for sale on the Internet, including accounts for most platforms and services, and armies of low-cost human labour for just about any task. Where once we believed in the wisdom of the crowd to guide us, and provide us with reliable insights, it’s now obvious that – in addition to the false amplification and dampening noted above – ratings and reviews for anything, anywhere can be bought.

What impact will this have, I wonder, as the very ratings and reviews that we’ve come to rely on to guide our purchasing decisions become ground zero for political campaigns and, more broadly, when rating become so polluted as to become worthless? What will the Web be like without reliable ratings in app stores, on movie and book review sites, or more insidiously on sites that review healthcare, education, legal services, and the like? It’s a dystopian future of the Web that I hope will remain safely in the pages of sci-fi novels.

Beyond reviews, these automation farms – whether powered by algorithms or “mechanical turks” via microtask marketplaces – expose the fragility of a Web enhanced by algorithms; a world where 15 seconds of Internet fame – placement on highly-coveted front page of curated social experience – is yours for a few hundred dollars or less. Need “soft articles” to improve your ranking or point of view? No problem (and surprisingly affordable!). Need sock puppet comments in a popular Internet forum? Ditto. Traffic to make your site appear more popular? Same. How is this wildly different than the idea of politically-motivated parties paying people to vote a certain way in elections?

This problem impacts everyone, and it’s getting bigger

I’ve avoided putting names to the platforms that this information pollution impacts because I believe that’s a distraction. Research can appear to be pointing fingers at one platform or another simply because that’s where data was most easily accessed, or scraped. However, there seem to be few, if any, limits to the spread of misinformation across the digital biospheres that now make up the larger ecosystem of the Internet. Here are just a few of the categories of challenges and signs that the problem is growing:

-

UX challenges. Many have pointed to the “UX problem” in the Facebook newsfeed: the issue is that much of the shared information looks the same, regardless of the source of the information. However, this is not a problem that impacts Facebook exclusively. Most platforms adopt UX patterns to help users navigate increasingly complex information streams, and most suffer from the same problem: Twitter, Google Plus, LinkedIn, etc. The open Web doesn’t excel here either because it’s very easy to spoof domains and copy the visual appearance of trusted news source. This is not an easy problem to solve in isolation, partly because of the risks of every platform introducing different approaches to addressing it.

-

Automated, algorithmic content creation, and AI. The implications here are terrifying. One researcher recently uncovered a small network of accounts on YouTube that had uploaded more than 80,000 videos, each generated by an algorithm that mixed news video and new article text to automatically create new videos (100s an hour). The motivation? YouTube by some measures is one of the larger search engines on the planet. Any platform that supports video – which is every platform now – is going to need to grapple with this. And the future is even more frightening, as video and audio manipulation reach new levels of fidelity. I wonder how initiatives like the shared industry hash database can prepare for this future?

-

Fake accounts. Whether automated or directed by people, there are signs of this pollution everywhere – from known disinformation peddlers setting up shop on publishing platforms like Medium to widespread false information on messaging platforms like WhatsApp – and there’s no end in sight. The moment a new service reaches a critical mass, there are shady vendors ready to sell friend requests, likes, dislikes, and more. Telegram, you ask? Yep. Periscope? Yessir. Not even Tinder is safe from fake accounts that aim to compromise user trust, privacy and security. Bots, automation, and low-cost digital labourers are everywhere.

Holy shit, this is a mighty big problem

That sounds dire, right? So, all that said, here are the three most important piece of information that I hope you will take away from this post:

-

Although the spotlight has been put on so-called “fake news,” the problem extends far beyond news and reaches into just about every aspect of our modern-day, digital lives. But understanding where it exists and how it works is critical to making progress on solutions, because – like contemporary approaches to fighting climate change – an effective response will need to be holistic. To that end, we need to identify and track the indicators of misinformation because that will help us measure the effectiveness of solutions.

-

Part of the challenge is that the various societal impacts we want to blame on misleading information – ideological polarization, increasing intolerance, and so on – are not easy to distill into convenient sound bites like “echo chambers,” “filter bubbles,” or “algorithmic bias.” For the past six months, I’ve been pouring over the academic research, convening events, attending events, and talking to anyone and everyone who is working on the issue. The summary? The problems herein are very complex. They are not easy to quantify and measure, and currently there’s conflicting research and opinion. Collaboration across platform companies is needed here to enable more research will help to move us toward a consensus.

-

Information pollution is a problem worth solving. Similar to big challenges that have faced humanity in the past and present – from health challenges like malaria or HIV, to basics like clean water, and even the tough ones like climate change – there is a reason to believe that we can meet this challenge and overcome it. In fact, we don’t have a choice because, quite simply, this epidemic of information pollution threatens the most powerfully-generative, socially-equalizing, shared global resource that humanity has ever known – the Internet. We need to keep meeting, talking, sharing resources and collaborating to build a movement around this issue.

If you’ve made it this far, you’re probably passionately interested in working on solutions to the most pressing threat to global democracy and the Internet – so here are a few practical ways that you can get involved:

-

Have a look at this calendar of events to see if there’s an upcoming event near you. If you know about an event that’s not listed, submit it so that others can learn more. And if there are no events in your area, let’s work together on creating one. Either way, please consider subscribing to the MisinfoCon mailing list for low-volume updates on events and initiatives in the space.

-

Have you read research that you believe is particularly illuminating, or points to a possible solution on any or all of the above? Please drop me a note. I’ll be publishing a summary of academic and industry papers that I believe are relevant reading for anyone who’s hoping to get up-to-speed quickly and I’d welcome your contributions to that undertaking (with attribution, of course!).

-

Are there datasets or tools – public or private – that you know about that would help to understand information pollution? Drop me a link. Similarly to the above, I’ll also be publishing a frequently-updated list of data that is being used in research, as well as tools that seek to address misinformation.

Last but not least, would you consider joining me in bringing a conversation about misinformation to this year’s Mozilla Festival in London, England? I am working with an incredible team of Mozillians to help shape the Open Innovation space at MozFest and we’d really welcome your submissions for a hands-on workshop, a talk, or a creative installation. Submission close on August 1st and the process to submit an idea take just a few minutes. Just mention @phillipadsmith in your submission and we can discuss the finer details over on GitHub.

Questions, comments, or insights on any of the above? You can find me in all the usual online places and say “hello.”

Thanks to Matt Thompson, Katharina Borchert, and Chris Lawrence for reading drafts of this, to Mozilla for funding my fellowship work on media, misinformation & trust, and to all of the individuals who’ve so generously gave their time to help me advance my understand of these complex issues (you know who you are).

About

Hi, I'm Phillip Smith, a veteran digital publishing consultant, online advocacy specialist, and strategic convener. If you enjoyed reading this, find me on Twitter and I'll keep you updated.

Related

Want to launch a local news business? Apply now for the journalism entrepreneurship boot camp

I’m excited to announce that applications are now open again for the journalism entrepreneurship boot camp. And I’m even more excited to ...… Continue reading

Previously

Here’s an opportunity to make progress on misinformation: track the indicators.

From the future

Do you know a reporter who has thought about starting a media business? Please share.